Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics. 2023. Vol. 20. N 3. P. 563–587.

Abstract

Children's development in the early years is significantly linked to further well- being. Among many factors involved in early development are mother’s attach- ment to the fetus and her emotional state during pregnancy. The current study prospectively explores mothers’ charac- teristics during the third trimester of pregnancy and their newborn children outcomes. The sample included 300 women with natural conception (NC) and 127 women with in-vitro fertilization (IVF), and their newborn children. For mothers, the following instruments were used: the Maternal Fetal Attachment Scale, the Clinical Scale for Self-assess- ment of Irritability, Depression and Anxiety. For newborns, the following parameters of newborn children outcomes were assessed: gestational period; the length and weight; the Apgar score in the first and fifth minutes after birth. All com- ponents of maternal attachment to the fetus were in the normal range for most women in both groups. All aspects of maternal attachment to the fetus were sig- nificantly greater in the IVF group. In both groups, more than 35% of women experi- enced depression and 43% of women expe- rienced moderate/severe levels of anxiety. In the NC group, greater scores on giving of self and enjoying of watching tummy jig- gle as the baby kicks inside were associated with less irritation in mothers. In the IVF group, the indicators of women’s attach- ment to their fetus were not associated with emotional states. Neither mothers’ attachment to their fetus nor their emo- tional states during pregnancy predicted newborn children outcomes. Children born from IVF had a statistically lower gestational period than in the NC group.

Introduction

Children’s mental development and health in the early years are significantly linked to further well-being. The complex system of factors contributing to chil- dren’s outcomes remains poorly understood. Whereas some factors have already been suggested as potential targets for early intervention and prevention programs (Keshishian et al., 2014; Solovyeva, 2014; Britto et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2018), many factors are still unclear.

Psychological readiness of a woman for motherhood, including mother’s attach- ment to the fetus, is one of such factors (Muntaziri Niyya, 2011; Alhusen et al., 2013; Solovyeva, 2014; Yakupova & Zakharova, 2016; Savenysheva, 2018; Cildir et al., 2020; Hruschak et al., 2022). Specifically, an increasing number of studies have shown that a mother’s attachment to the fetus can affect the relationship between mother and child, the formation of parental identity and the child’s future social, emotional and cognitive development (Ranson & Urichuk, 2008; Talykova, 2008; Gracka-Tomaszewska, 2010; Vasilenko & Vorobeva, 2016; Foley & Hughes, 2018). The emotional connection of the mother with the fetus is manifested in parental care for the child already during pregnancy when the mother engages in well-being promoting behaviors. These include proper nutrition, sleep and exercise, absten- tion from substance use, as well as the developing mindfulness skills during preg- nancy and desire to get acquainted with the fetus during pregnancy (Lindgren, 2001; Eastwood et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Nyklček et al., 2018).

Psychological readiness of a woman for motherhood, including mother’s attach- ment to the fetus, is one of such factors (Muntaziri Niyya, 2011; Alhusen et al., 2013; Solovyeva, 2014; Yakupova & Zakharova, 2016; Savenysheva, 2018; Cildir et al., 2020; Hruschak et al., 2022). Specifically, an increasing number of studies have shown that a mother’s attachment to the fetus can affect the relationship between mother and child, the formation of parental identity and the child’s future social, emotional and cognitive development (Ranson & Urichuk, 2008; Talykova, 2008; Gracka-Tomaszewska, 2010; Vasilenko & Vorobeva, 2016; Foley & Hughes, 2018). The emotional connection of the mother with the fetus is manifested in parental care for the child already during pregnancy when the mother engages in well-being promoting behaviors. These include proper nutrition, sleep and exercise, absten- tion from substance use, as well as the developing mindfulness skills during preg- nancy and desire to get acquainted with the fetus during pregnancy (Lindgren, 2001; Eastwood et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Nyklček et al., 2018).

Prenatal attachment can contribute to the child’s positive development, which has been shown in a number of studies describing the effectiveness of maternity protection programs (Hompes et al., 2012; Dokuhaki et al., 2019). These programs were aimed at strengthening prenatal attachment through raising awareness and improving interaction with the fetus. In the intervention group, educating the women on fetal-maternal attachment skills was associated with the infants’ earlier achievement of some gross and fine motor skills, such as the equal hand movement, with modest to moderate effects at one and three months of age (Dokuhaki et al., 2017). In another study, attachment skills of mothers were related to greater chil- dren’s height and weight, compared to the control group at birth, and one month and three months after birth (Maddahi et al., 2016).

Many studies found that pregnant women on average report higher rates of depression, irritability, anxiety, and high mood instability than non-pregnant women (Bowen et al., 2012; Yazici et al., 2018; Bahadırlı et al., 2019). Several stud- ies demonstrated that depression during pregnancy may lead to maternal behaviors that present a risk for low birth weight, and poor physical and mental health of the child (Vasilenko & Vorobeva, 2016; Eastwood et al., 2017; Robbins, 2003; Petrova et al., 2013). For example, the association between depression and birth weight was found in a retrospective study of mothers (N = 17564) of all infants born in public health facilities of New South Wales (NSW). Children of mothers with higher scores for antenatal depressive symptoms, measured with Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, had higher odds of low birth weight [OR = 1.7] and of a shorter gestational age at birth of < 37 weeks [OR = 1.3], compared to children of women with lower depression scores (Eastwood et al., 2017). Thus, in a prospective cohort study of 681 women in France were found that the rate of spontaneous preterm birth was significantly higher among women with higher depression scores (9.7%), as opposed to other women (4.0%), even after adjustment for potential confound- ing factors (Dayan et al., 2006). In a study from New Zealand, women at increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth have higher levels of anxiety (Dawes et al., 2022). Some studies have demonstrated that anxiety, bad mood and stress in early and late pregnancy can affect the fetus’ development and somatic well-being (Punamaki et al., 2006; Qiao et al., 2012; Brunton, 2013).

Research suggests that attachment to the fetus may mediate the links between mothers’ emotional states and newborn children outcomes. However, results of previous studies are inconsistent regarding these links during pregnancy, as well as the directions of causation (Della Vedova & Burro, 2017). Several studies reported that attachment to the fetus was negatively related to anxiety and depression (Hart & McMahon, 2006; Hjelmstedt et al., 2006; Della Vedova & Burro, 2017). Other studies found no link between attachment and mental health (Hjelmstedt etal., 2006; McFarland et al., 2011). Yet, other research suggests that anxiety about an abnormality of the fetus or the risk of premature birth strengthens attachment, lead- ing to positive correlation between them (Abazari et al., 2017). For example, a study found that pregnant women with mild depressive symptoms paid more attention to fetal movements than women without depression (Seimyr et al., 2009).

Currently, parental attitudes and emotional states of women participating the IVF program are actively studied, suggesting that these women require psychological sup- port both during the pregnancy and after childbirth (Malenova & Kytkova, 2015; Yakupova & Zakharova, 2016). Research has suggested that women with IVF show on average greater attachment to the baby. For example, a study found that women in the IVF group on average had higher rates of attachment to the fetus and subsequent- ly to the baby than women in the group with natural conception (Chen et al., 2011). However, some studies did not find average differences in mothers’ attachment to their unborn children regardless of the type of conception (Hopkins et al., 2018).

Some research found that emotional states of women participating in the in- vitro fertilization procedure are characterized by a significant frequency of affec- tive disorders, comorbidity of anxiety and depression, such as predominant disor- ders of the anxiety spectrum, as well as lower indicators of well-being, activity, and mood, compared to women with a physiologically natural pregnancy (Petrova, Podolkhov, 2011; Petrova et al., 2013). For example, it was shown in a study that almost a third of women with IVF have symptoms of mild, moderate, and, in a few cases, severe depression (Naku et al., 2016). Another study found that women using IVF reported significantly greater anxiety about losing a pregnancy than about the baby’s possible health, compared to women having a natural conception (Hjelmstedt et al., 2003). The elevated rate of psychological problems in women who use in-vitro fertilization may be partly related to their history of infertility (Hjelmstedt et al., 2003; Petrova, Podolkhov, 2011; Petrova et al., 2013). However, other research did not find differences between IVF and natural conception groups. For example, most women participating in an IVF program were found to have an average level of anxiety (Naku et al., 2016).

Overall, the gaps in the existing literature underline the need for research inves- tigating the association between maternal factors, such as prenatal attachment to the fetus and emotional states, and newborn children outcomes.

Aim

The current study prospectively explores mothers’ psychological characteristics during the third trimester of pregnancy and their newborn children outcomes. The study has the following three aims:

1. To investigate potential differences between the NC and IVF groups in: 1.1 maternal attachment during pregnancy;

1.2 emotional states of women during pregnancy;

1.3 newborn children outcomes.

2. To investigate links among groups of variables in the NC and IVF groups: 2.1 attachment characteristics;

2.2 mothers’ emotional states;

2.3 maternal attachment and mothers’ emotional states; 2.4 newborn children outcomes.

3. To explore the links between mothers’ psychological characteristics in preg- nancy and newborn outcomes in the NC and IVF groups:

3.1 maternal attachment and mothers’ emotional states with newborn chil- dren outcomes;

3.2 a potential mediating role of maternal attachment in the links between mothers’ emotional states and newborn children outcomes.

1. To investigate potential differences between the NC and IVF groups in: 1.1 maternal attachment during pregnancy;

1.2 emotional states of women during pregnancy;

1.3 newborn children outcomes.

2. To investigate links among groups of variables in the NC and IVF groups: 2.1 attachment characteristics;

2.2 mothers’ emotional states;

2.3 maternal attachment and mothers’ emotional states; 2.4 newborn children outcomes.

3. To explore the links between mothers’ psychological characteristics in preg- nancy and newborn outcomes in the NC and IVF groups:

3.1 maternal attachment and mothers’ emotional states with newborn chil- dren outcomes;

3.2 a potential mediating role of maternal attachment in the links between mothers’ emotional states and newborn children outcomes.

Participants

The sample included 300 women with natural conception (NC) and 127 women with in-vitro fertilization (IVF), and their newborn children. All of them are par- ticipants in the Prospective Longitudinal Interdisciplinary Study (PLIS). The study included women with a single (not multiple) pregnancy. The average age of women in the NC group was 29.3 ± 4.0 years; in the IVF group, 33.2 ± 4.6 years. The average gestation period in the NC group was 39.89 ± 1.26; in the IVF group, 38.57 ± 2.04. In the NC group, 16.7% of women noted that their pregnancy was unplanned. In each group, a certain number of women already had children (it was not their first pregnancy and childbirth): one child, 27.3% in the NC group and 22.0% in the IVF group; two children, 4.0% in the NC group and 3.9% in the IVF group; three children, 1.0% in the NC group and .9% in the IVF group.

Procedure

Data collection was carried out at obstetric clinics and assisted reproductive technology centers in Siberian region (Russia). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Interdisciplinary Research at Tomsk State University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study, including for accessing their medical records. Data were collected from participants in the third trimester of pregnancy, as well as from perinatal and postnatal medical records (in medical centers where pregnancy monitoring and delivery were conducted).

Measures

Mothers’ Psychological Characteristics

Two instruments were used to evaluate psychological characteristics of preg- nant women: the Maternal Fetal Attachment Scale (Cranley, 1981) and the Clinical Scale for Self-assessment of Irritability, Depression and Anxiety (IDA- Scale; Snaith, 1978). The instruments are based on the materials of a large-scale longitudinal study of child development, the C-IVF (Cardiff Study of IVF Children, UK). The measures were adapted to Russian using the following proce- dure: two independent translators, whose first language is Russian and the second English, conducted the translation of the test from English to Russian following the ITC guidelines for test translations (International Test Commission, 2017).

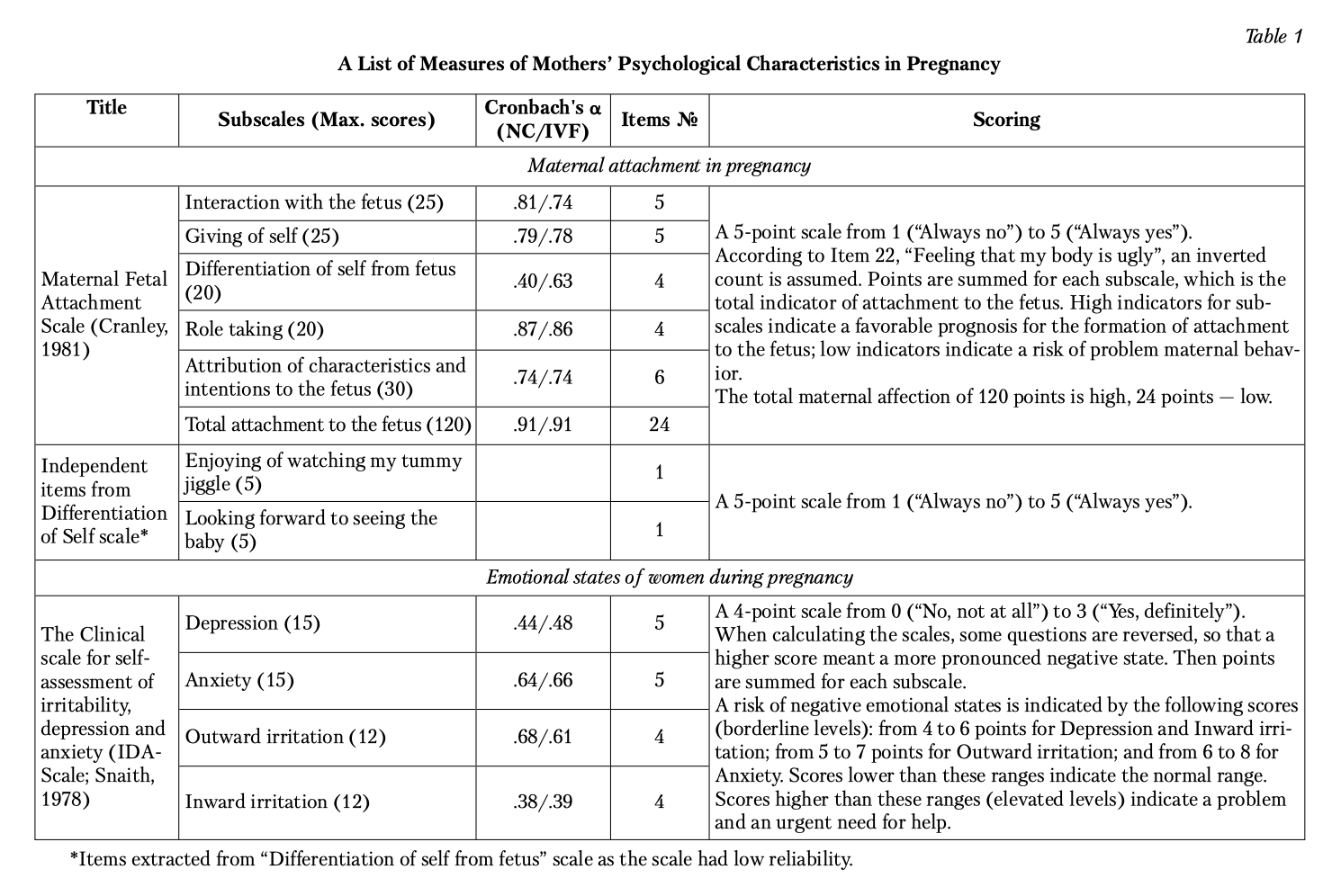

Table 1 provides a description and reliability information (Cronbach’s alpha) for each subscale. As can be seen from Table 1, low reliability was found for the Differentiation of self from fetus subscale of the attachment scale. We explored the poor reliability of this subscale. Two items (Decision on the name for a baby girl; Decision on the name for a baby boy) had low loading on the subscale. We removed these items from the subscale and used the remaining two items of the subscale as separate independent variables.

For emotional states, low reliability was found for two subscales: Depression and Inward irritation (see Table 1). The IDA was originally created for self-assess- ment of emotional states in a clinical context and showed high reliability. For example, Cronbach’s alpha among patients with Huntington’s disease was between .87 and .90 for Depression, Anxiety, Outward and Inward irritation. Some studies with non-clinical populations used modified versions of the IDA scale, for example excluding self-harm items, leading to better reliability (.71–.81) (Wilson et al., 2019). We decided to keep the original subscales, despite the poor internal consis- tency of times, because the summed up total scores provide a reasonable measure of individual differences for this research purpose.

Newborn Children Outcomes

Table 2 presents the description for the five parameters of newborn children outcomes obtained from mothers’ medical records, as well as normative values for these parameters.

Statistical Analysis

We used the following methods: descriptive statistics, Mann-Whitney U test, Chi squared analysis, Spearman nonparametric correlation criterion, regression analysis, and mediation analysis (in the IBM SPSS Statistics 26 application package).

Results

Statistically significant differences in the age of the study participants were revealed: women of the IVF group are older than women with natural conception (U = 9350.5; p < .01).

Group comparisons

Maternal attachment to the fetus in the NC and IVF groups

The NC and IVF groups were compared for indicators of maternal attachment to the fetus in the third trimester of pregnancy. As the distributions differed from normal, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used. The results presented in Table 3 showed significant statistical differences between the NC and IVF groups. The IVF group showed on average greater maternal attachment on all sub- scales compared to the NC group. The effect size of the differences was weak, but remained significant after correction for multiple comparisons (p = .05/7 = .007), with the exception for Parameter 7, Enjoying of watching my tummy jiggle.

Emotional states among women in the NC and IVF groups

Table 4 presents descriptive statistics for women’s emotional states in the third trimester of pregnancy in the NC and IVF groups. Regardless of the type of conception, more than 35% of women experienced borderline or elevated levels of depression and more than 43% of women experienced moderate/severe levels of anxiety. More women experienced outward irritation (20.7–30.7%) than inward irritation (1.2–4.1%).

The Mann-Whitney U test between the NC and IVF groups showed no signif- icant differences for any indicators of emotional states, with the exception of Outward irritation, which was more pronounced in the NC group (U = 9645.50, p = .05). The effect size (Eta squared (2) = .011, dCohen = 0.207) was negligible and significance did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (p = .05/4 = .013).

The Mann-Whitney U test between the NC and IVF groups showed no signif- icant differences for any indicators of emotional states, with the exception of Outward irritation, which was more pronounced in the NC group (U = 9645.50, p = .05). The effect size (Eta squared (2) = .011, dCohen = 0.207) was negligible and significance did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (p = .05/4 = .013).

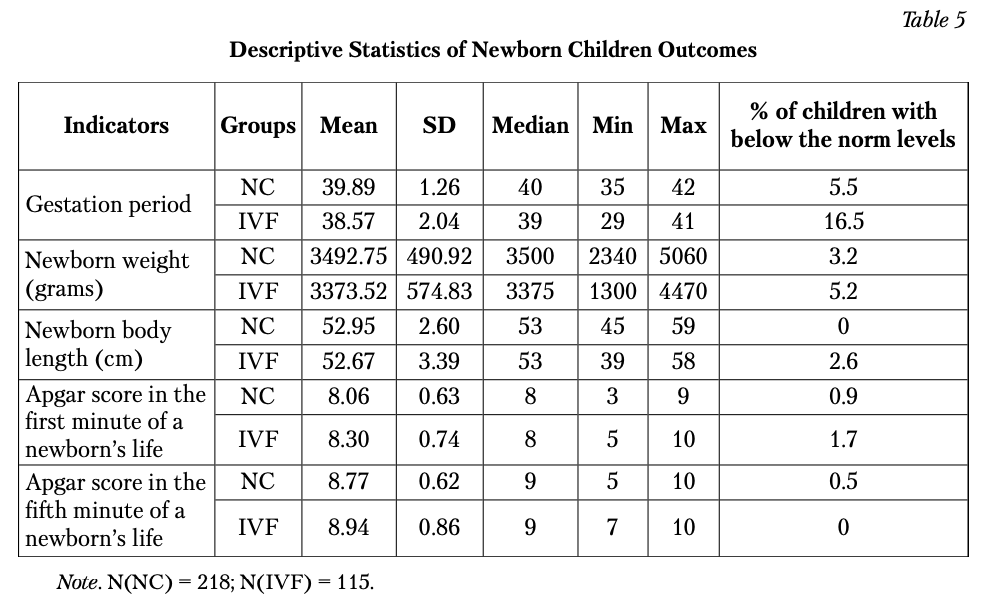

Newborn children outcomes in the NC and IVF groups

Table 5 presents descriptive statistics for newborn children outcomes. According to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion, in both groups, the distribution of all indica- tors differed from normal, with the exception of the weight of newborns in the NC group. The gestation period results indicated that for most children, birth occurred in a standard time frame. However, about one in six of the IVF children had a gestational period below normal. Indices on the Apgar scale in the first and fifth minutes of a child’s life, newborn weight and body length were within the norm for most children.

Comparative analysis using the Mann-Whitney and Chi squared tests is pre- sented in Table 6. The results of the Mann-Whitney U test indicate that children born from IVF have a statistically lower gestational period than children in the NC group (after correction for multiple comparisons: p = .05/5 = .01). Sizes were moder- ate to large. There were no significant differences for the newborn weights and length, and the Apgar scale indicators. Chi squared analyses performed on categorical data (frequencies below norm levels) showed significant differences in the gestation period.

Comparative analysis using the Mann-Whitney and Chi squared tests is pre- sented in Table 6. The results of the Mann-Whitney U test indicate that children born from IVF have a statistically lower gestational period than children in the NC group (after correction for multiple comparisons: p = .05/5 = .01). Sizes were moder- ate to large. There were no significant differences for the newborn weights and length, and the Apgar scale indicators. Chi squared analyses performed on categorical data (frequencies below norm levels) showed significant differences in the gestation period.

Links among the Variables

Maternal attachment characteristics in the NC and IVF groups

In both groups, most correlations among different indicators of maternal attachment to the fetus were significant (ranging from .24 to .60). Out of 15 pairwise correlations, when adjusted for multiple comparisons (p = .05/20 = .003), six were not signifi- cant in the IVF group (see Table 7). Five of the 15 correlations were stronger in the NC group (Fisher-Z transformation).

Mothers’ emotional states in the NC and IVF groups

All indicators of emotional states were significantly correlated in the NC group (ranging from .22 to .35), including after multiple testing (p = .05/6 = .008) cor- rection (Table 8). In the IVF group, three significant correlations were found after multiple testing. Anxiety was not significantly associated with other emotional states. No significant differences were found between the two groups in the corre- lation coefficients.

Maternal attachment and mothers’ emotional states in the NC and IVF groups

Spearman nonparametric correlations did not differ significantly between the NC and IVF groups (Table 9). In both groups, Giving of self was weakly but signif- icantly negatively correlated with Depression and Anxiety; in the IVF group, Role taking had a significant negative correlation with Inward irritation; in the NC group, Enjoying of watching my tummy jiggle had a significant negative correla- tion with Depression and Outward irritation, but these correlations did not sur- vive the multiple testing correction (p = .05/33 = .002). The results showed three significant correlations (after multiple correction adjustment) in the NC group: Giving of self negatively correlated with Outward and Inward Irritation; Enjoying of watching my tummy jiggle negatively correlated with Inward irritation.

Newborn children outcomes in the NC and IVF groups

The results of the Spearman’s test presented in Table 10 revealed expected pos- itive significant correlations between the majority of indicators of development in both groups (including after correction for multiple comparisons (p = .05/10 = .005)). In several cases, the correlations were statistically higher in the IVF group than in the NC group.

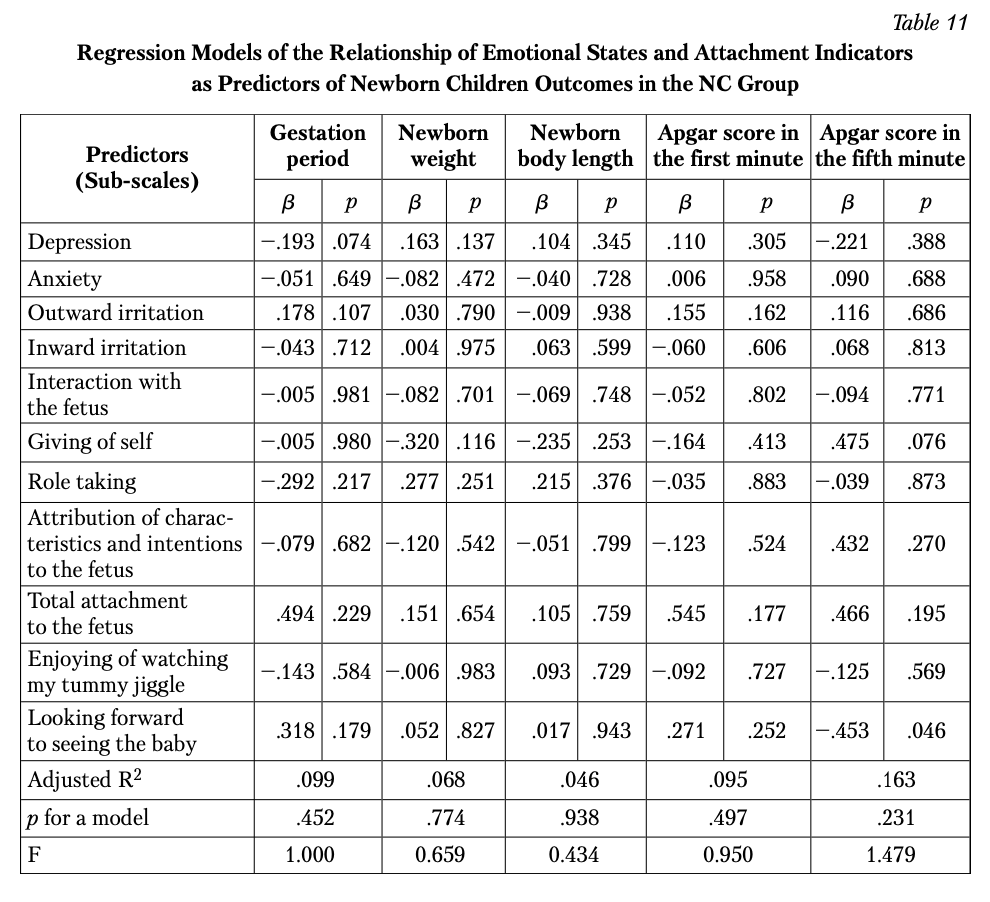

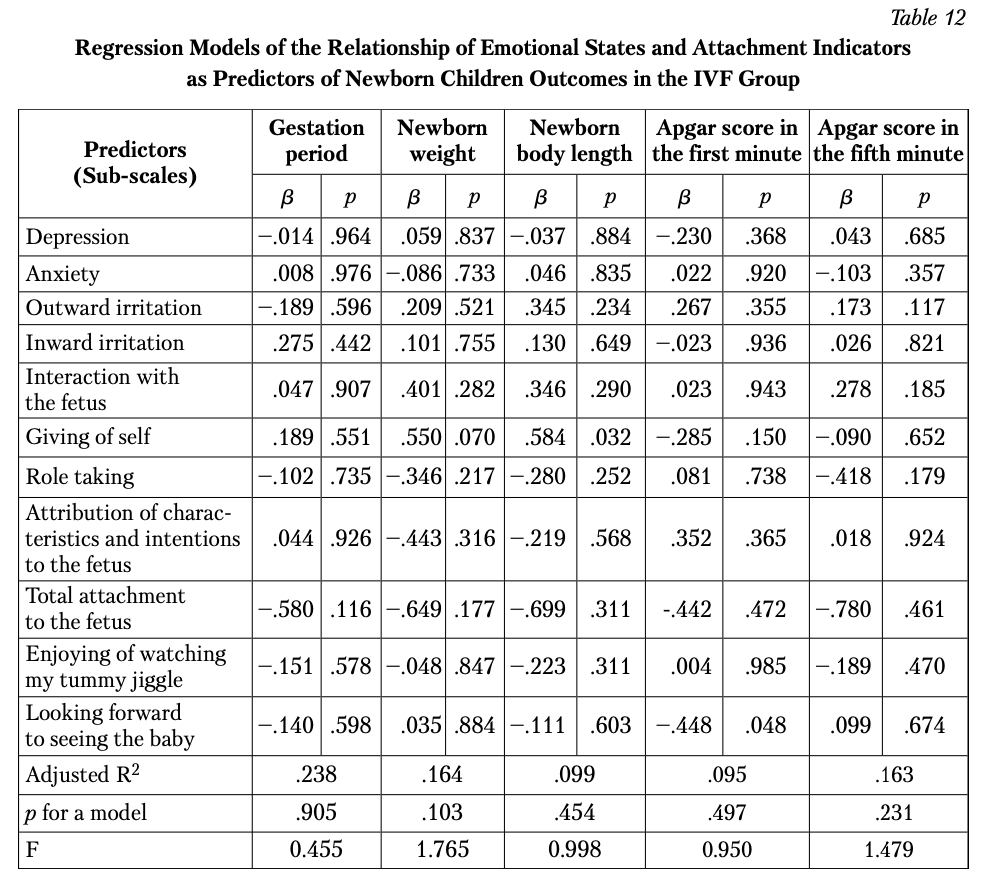

Mothers’ Emotional States and Attachment to the Fetus during Pregnancy and Newborn Children Outcomes

We performed regression analyses (the Enter method) to assess the links between mothers’ measures (emotional states and attachment during pregnancy) and the newborn children outcomes. There were a series of regressions with five newborn children outcomes as criterion variables: body length, weight, gestational period, and Apgar score in the first and fifth minutes. In all five models, mothers’ emotional states and attachment to the fetus were simultaneously entered into the regression as 11 predictor variables. Tables 11 and 12 present the results of these regressions for both groups. None of the models were significant.

We further explored the hypothesized mediating role of attachment in the links between mothers’ emotional states and newborn children outcomes. We performed the analysis of mediation using the PROCESS Procedure for SPSS Release 2.16.1. We found no evidence for a mediating role of attachment between emotional states and newborn children outcomes in both groups.

We further explored the hypothesized mediating role of attachment in the links between mothers’ emotional states and newborn children outcomes. We performed the analysis of mediation using the PROCESS Procedure for SPSS Release 2.16.1. We found no evidence for a mediating role of attachment between emotional states and newborn children outcomes in both groups.

Discussion

The present study is part of a large-scale longitudinal project following groups with in-vitro fertilization and natural conception (from the period of pregnancy to children’s admission to school). The revealed statistically significant differences in the age of the study participants repeat the established conclusion about the aver- age greater age of mothers with IVF in comparison with women with NC. The analyses explored maternal emotional states in the third trimester of pregnancy as they relate to newborn children outcomes.

First, we explored absolute levels of maternal attachment to the fetus (as the extent to which women engage in behaviors that represent an affiliation and inter- action with their unborn child) and found that most women showed attachment levels in the normal range. The results were consistent with previous literature on samples from other populations (Hjelmstedt et al., 2006; Karatas et al., 2011; Lingeswaran & Bindu, 2012; Alhusen et al., 2012). We then investigated potential differences in maternal attachment in pregnancy between the NC and IVF groups. We found that attachment was significantly higher in women in the IVF group. Thus, women in the IVF group are more likely than women with a natural concep- tion to talk to their unborn child, refer to the baby by a nickname, stroke the baby’s tummy to quiet them when there is too much kicking. Women with IVF feel stronger that all the trouble of being pregnant is worth it, try to do things to stay healthy that they would not do if they were not pregnant, give up doing certain things (alcohol consumption, smoking, etc.).

Also, the following is more character- istic for women of this group, compared with women with natural conception: they imagine themselves feeding and taking care of the baby, can hardly wait to hold the baby, look forward to seeing what the baby looks like. Women with IVF are more likely to attribute characteristics and intentions to their unborn child: to wonder if the baby feels cramped in there, can almost guess what the baby’s personality will be from the way they move around, wonder if the baby can hear, can tell that the baby has the hiccoughs. This is consistent with a study of Chen et al. (2011). However, other studies did not find greater attachment in the IVF groups (Hjelmstedt et al., 2006; Hammarberg et al., 2008; Hopkins et al., 2018). These inconsistencies may be explained by differences across the studies in the sample size; pregnancy trimester of assessment and measures used to assess prenatal attachment.

In both groups, almost all indicators of maternal attachment to the fetus were related to each other, with some stronger correlations and with more correlations in the NC group (with stronger intensity of this indicators in the IVF group described above). This may define a lower consistency of the components of mater- nal attachment to the fetus in the IVF group compared with women with natural conception due to the presence of unpleasant symptoms during pregnancy, and tap into complex feelings during pregnancy: fears of the upcoming birth; doubting one’ parenting abilities; worry about child’s health; experience of one’s bodily metamor- phosis and the associated feeling of one’s unattractiveness, as well as necessary changes in one’s lifestyle. Unlike in the NC group, the correlation between Enjoying of watching my tummy jiggle with other indicators of maternal attach- ment was not significant in the IVF group. Enjoying of watching my tummy jiggle is focused on enjoying experiencing the baby’s activity in the womb and imagining the baby’s feelings and thoughts as it is developing in the womb, but probably for a woman with IVF, it does not define engaging in behaviors that represent an affil- iation and interaction with the unborn child. Also, Giving of self, which means that pregnant women feel that all the trouble of being pregnant is worth it, because she is pregnant and she does things to improve her well-being and wellbeing of the baby inside, is not significantly associated with Attributing characteristics and intentions to the fetus. The results indicating the difference in the levels of severity and interrelationships of indicators of maternal attachment to the unborn child in the IVF group (as opposed to the NC group) have prognostic significance and can be considered as indicators of maternal attitude to the child after childbirth in the process of care, upbringing and interaction with them.

Next, we explored mothers’ levels on the four dimensions: depression, anxiety, and outward and inward irritation. In both groups, more than 35% of women expe- rienced borderline or elevated levels of depression and more than 43% of women experienced moderate/severe levels of anxiety. These women don’t feel cheerful, have poor appetite, can’t laugh or feel amused, haven’t kept up their old interests, wake up ahead of time, get scared or panicky for no good reason, can’t sit down and relax quite easily, feel tense or “wound up”, can’t go out on their own without feel- ing anxious, so might require psychological support to alleviate the symptoms and buffer the potential negative effect on their infants. Inward irritation was low in women of both groups; it means that it is not typical for the overwhelming majority of the study participants to get angry with themselves or call themselves names, feel like harming themselves, be getting annoyed with themselves. There were increased levels of outward irritation in 20.7-30.7% of women: they could lose tem- per, yell and snap at others, lose control and hit or hurt someone, and be less patient with other people. Overall, these results are consistent with findings of several pre- vious studies that showed higher levels of irritability and mood instability in preg- nant as compared to non-pregnant women (Hjelmstedt et al., 2006; McMahon et al., 2007; Yazici et al., 2018). The multiple comparisons in our study showed that the groups did not statistically differ for depression, anxiety, and outward and inward irritation. As described in the introduction, previous research into the group difference is inconsistent (Hjelmstedt et al., 2003; McMahon et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2011; Hopkins et al., 2018). Our results suggest that women regardless of the type of conception show very similar emotional states during pregnancy. In the IVF group (compared to the NC group) anxiety was not significantly associat- ed with other emotional states, which may reflect certain specifics about the weak interrelationship and interdependence of negative emotional states of this group of pregnant women in the last trimester of pregnancy and reflect the need to search for factors causing such specifics.

The results of the correlation analysis for indicators of maternal attachment to the fetus and indicators of emotional states showed that in the IVF group, unlike in the NC group, there are no significant relationships. In the NC group, Giving of self showed significant negative relationships with Outward and Inward irritation, Enjoying of watching my tummy jiggle showed significant negative correlation with Outward and Inward irritation. Women who are more irritated with them- selves and the world around them are less responsible for the child’s life, and are less willing to sacrifice their comfort and pleasure for the sake of strengthening the child’s health. Also, women who are more irritated with themselves are less able to enjoy watching their tummy jiggle. Similarly to the group with NC, in the IVF group, depression and anxiety, for which more than a third of women in each group have borderline and elevated levels, are in no way related to indicators of maternal attachment to the fetus. These data differ from the results of some other studies in which correlations were found, for example in Hart & McMahon, 2006; Hjelmstedt et al., 2006; Della Vedova & Burro, 2017; Seimyr et al., 2009; Abazari et al., 2017. Further research is needed to clarify the possible factors that determine the pres- ence/absence of such relationships and their causal mechanisms.

Our analyses of the potential differences in newborn children outcomes showed that, on average, infants in the IVF group had a shorter gestation period than in the NC group, in compliance with norms for the gestational period. Only 16.5% of the IVF group children had gestational period indicators below the norm. There are also studies showing differences in newborn children outcomes, depending on the type of conception. For example, Stojnic et al. (2013) showed that the mean gesta- tional age at delivery of the IVF group was 38.13 ± 1.72 weeks, slightly shorter than 38.65 ± 1.79 weeks in spontaneously conceived singletons. In general, it can be concluded that pregnancy with IVF can potentially increase the perinatal risk of premature birth for some of the women who have used this method. Despite this, there were no significant group differences between NC and IVF children in new- born weight and length, and health as measured by the Apgar scores, which is sim- ilar to the results of some studies, for example Belva et al. (2007) and Tomic (2011). For child characteristics, in the IVF group, all newborn children outcomes were linked to each other. Fewer associations were observed in the NC group: the child gestational period was associated with body length and weight; two Apgar scales were associated with each other, but not with other newborn children out- comes. Overall, in the IVF group, the associations among the newborn children outcomes were stronger than in the NC group.

We found that in both NC and IVF groups none of the maternal emotional states or attachment characteristics were significantly associated with newborn children outcomes. This result is inconsistent with some previous research that found such associations. This inconsistency may stem from the fact that most pre- vious research considered overall mother-fetus attachment, rather than specific components of attachment to the fetus (Alhusen et al., 2012; Stojnic et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2019; Simpson et al., 2019). Studies that examined individual com- ponents of prenatal attachment found that only some of them were weakly corre- lated with newborn children outcomes (Wilson et al., 2019). Moreover, the links between prenatal attachment and newborn children outcomes may be mediated by health practices during pregnancy (Alhusen et al., 2012). This should be further investigated. Finally, the mediation analysis performed in the present study did not find evidence that prenatal attachment mediates the links between mothers’ emo- tional states and newborn children outcomes. Given that these factors can be asso- ciated with child’s later development and maternal postpartum parental attitudes (Shreffler et al., 2021; Savenysheva et al., 2022), the observed results could be implemented in a complex system of psychological support for women with IVF. So, the data presented in the article complement the available scientific data obtained from various socio-cultural samples and serve as a basis for further research, since the problem under study has not received an unambiguous solution, and an expanded search for factors that may directly or indirectly affect the studied relationships is required.

Conclusion

The study found that maternal attachment to the fetus is more pronounced in the IVF group compared to the NC group of mothers. In contrast, no group differ- ences were found in mothers’ depression, anxiety, outward and inward irritation during the third trimester of pregnancy. In the IVF group, no significant correla- tions of indicators of maternal attachment and emotional states were found. In the NC group, higher scores on giving of self and greater enjoying of watching tummy jiggle as the baby kicks inside were associated with less irritation of pregnant women. Children born from IVF had statistically a lower gestational period; how- ever, these groups did not differ in body weight and length, and the Apgar scores, as compared to children in the NC group. No associations were found between mothers’ prenatal attachment, emotional states and newborn children outcomes.

a) National Research Tomsk State University, 36 Lenina Str., Tomsk, 634050, Russian Federation

b) Siberian State Medical University, 2 Moskovsky Trakt Str., Tomsk, 634050, Russian Federation

c) FBSSI Psychological Institute of the Russian Academy of Education, 9, Bld 4, Mokhovaya Str., Moscow, 125009, Russian Federation

d) Goldsmiths, University of London, London SE14 6NW, United Kingdom

b) Siberian State Medical University, 2 Moskovsky Trakt Str., Tomsk, 634050, Russian Federation

c) FBSSI Psychological Institute of the Russian Academy of Education, 9, Bld 4, Mokhovaya Str., Moscow, 125009, Russian Federation

d) Goldsmiths, University of London, London SE14 6NW, United Kingdom

References

Abazari, F., Pouraboli, B., Tavakoli, P., Aflatoonian, M., & Kohan, M. (2017). Anxiety and its relation- ship with maternal-fetal attachment in pregnant women in Southeast of Iran. i-manager’s Journal on Nursing, 7(3), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.26634/jnur.7.3.13788

Alhusen, J. L., Gross, D., Hayat, M. J., Woods, A. B., & Sharps, P. W. (2012). The influence of mater- nal-fetal attachment and health practices on neonatal outcomes in low-income, urban women. Research in Nursing & Health, 35(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21464

Alhusen, J. L., Hayat, M. J., & Gross, D. (2013). A longitudinal study of maternal attachment and infant developmental outcomes. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(6), 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0357-8

Bahadırlı, A., Sönmez, M. B., Memi , Ç. Ö., Bahadırlı, N. B., Memi , S. D., Dogan, B., & Sevincok, L. (2019). The association of temperament with nausea and vomiting during early pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 39(7), 969–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2019.1581745

Belva, F., Henriet, S., Liebaers, I., van Steirteghem, A., Celestin-Westreich, S., & Bonduelle, M. (2007). Medical outcome of 8-year-old singleton ICSI children (born >or=32 weeks’ gestation) and a spontaneously conceived comparison group. Human Reproduction, 22(2), 506–515. https://doi.org/10.1093/Humrep/Del372

Bowen, A., Bowen, R., Balbuena, L., & Muhajarine, N. (2012). Are pregnant and postpartum women moodier? Understanding perinatal mood instability. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 34(11), 1038–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35433-0

Britto, P. R., Lye, S. J., Proulx, K., Yousafzai, A. K., Matthews, S. G., Vaivada, T., Perez-Escamilla, R., Rao, N., Ip, P., Fernald, L. C. H., MacMillan, H., Hanson, M., Wachs, T. D., Yao, H., Yoshikawa, H., Cerezo, A., Leckman, J. F., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2017). Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. Lancet, 389(10064), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3

Brunton, P. J. (2013). Effects of maternal exposure to social stress during pregnancy: consequences for mother and offspring. Reproduction, 146, 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-13-0258

Chen, C. J., Chen, Y. C., Sung, H. C., Kuo, P. C., & Wang, C. H. (2011). Perinatal attachment in natu- rally pregnant and infertility-treated pregnant women in Taiwan. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(9), 2200–2208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05665.x

Cildir, D. A., Ozbek, A., Topuzoglu, A., Orcin, E., & Janbakhishov, C. E. (2020). Association of prenatal attachment and early childhood emotional, behavioral, and developmental characteristics: A longi- tudinal study. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(4), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21822

Cranley, M. S. (1981). Maternal Fetal Attachment Scale (MFAS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t06786-000

Dawes, L., Waugh, J. J. S., Lee, A., & Groom, K. M. (2022). Psychological well-being of women at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth cared for in a pecialized preterm birth clinic: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open, 12(3), Article e056999. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056999

Dayan, J., Creveuil, C., Marks, M. N., Conroy, S., Herlicoviez, M., Dreyfus, M., & Tordjman, S. (2006). Prenatal depression, prenatal anxiety, and spontaneous preterm birth: a prospective cohort study among women with early and regular care. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(6), 938–946. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000244025.20549.bd

Della Vedova, A. M., & Burro, R. (2017). Surveying prenatal attachment in fathers: the Italian adap- tation of the Paternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (PAAS-IT). Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 35(5), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2017.1371284

Dokuhaki, S., Akbarzadeh, M., & Heidary, M. (2019). Investigation of the effect of training attachment behaviors to pregnant mothers on some physical indicators of their infants from birth to three months based on the separation of male and female infants. Pediatrics and Neonatology, 60(3), 324– 331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedneo.2018.08.002

Dokuhaki, A., Akbarzadeh, M., Pishva, N., & Zare, N. A. (2017). A study of the effect of training preg- nant women about attachment skills on infants’ motor development indices at birth to four months. Family Medicine & Primary Care Review, 19(2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.5114/fmpcr.2017.67864

Eastwood, J., Ogbo, F. A., Hendry, A., Noble, J., & Page, A. (2017). The impact of antenatal depression on perinatal outcomes in Australian women. PLoS ONE, 12(1), Article e0169907. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169907

Foley, S., & Hughes, C. (2018). Great expectations? Do mothers’ and fathers’ prenatal thoughts and feelings about the infant predict parent-infant interaction quality? A meta-analytic review. Developmental Review, 48, 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.03.007

Gracka-Tomaszewska, M. (2010). Psychological factors during pregnancy correlated with infant low birth weight. Pediatric Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, 16(3), 216–219. (in Polish)

Hammarberg, K., Fisher, J. R., & Wynter, K. H. (2008). Psychological and social aspects of pregnancy, childbirth and early parenting after assisted conception: a systematic review. Human Reproduction Update, 14(5), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmn030

Hart, R., & McMahon, C. A. (2006). Mood state and psychological adjustment to pregnancy. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9, 329–337. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-006-0141-0

Hjelmstedt, A., Widström, A. M., & Collins, A. (2006). Psychological correlates of prenatal attachment in women who conceived after in vitro fertilization and women who conceived naturally. Birth, 33, 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00123.x

Hjelmstedt, A., Widstrom, A. M., Wramsby, H., Matthiesen, A. S., & Collins, A. (2003). Personality factors and emotional responses to pregnancy among IVF couples in early pregnancy: a compara- tive study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 82, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00040.x

Hompes, T., Vrieze, E., Fieuws, S., Simons, A., Jaspers, L., Bussel, J. V., Schops, G., Gellens, E., Bree, R. V., Verhaeghe, J., Spitz, B., Demyttenaere, K., Allegaert, K., den Bergh, B. V., & Claes, S. (2012). The influence of maternal cortisol and emotional state during pregnancy on fetal intrauterine body length. Pediatric Research, 72(3), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2012.70

Hopkins, J., Miller, J. L., Butler, K., Gibson, L., Hedrick, L., & Boyle, D. A. (2018). The relation between social support, anxiety and distress symptoms and maternal fetal attachment. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36(4), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2018.1466385

Hruschak, J. L., Palopoli, A. C., Thomason, M. E., & Trentacosta, C. J. (2022). Maternal-fetal attach- ment, parenting stress during infancy, and child outcomes at age 3 years. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(5), 681–694. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.22004

International Test Commission. (2017). The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (2nd ed.). https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation_2ed.pdf

Karatas, J. C., Barlow-Stewart, K., Meiser, B., McMahon, C., Strong, K. A., Hill, W., Roberts, C., & Kelly, P. J. (2011). A prospective study assessing anxiety, depression and maternal-fetal attachment in women using PGD. Human Reproduction, 26(1), 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq281

Keshishian, E. S., Tsaregorodtsev, A. D., & Ziborova, M. I. (2014). The health status of children born after in vitro fertilization. Rossiiskii Vestnik Perinatologii i Pediatrii [Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics], 59(5), 15–25. (in Russian)

Lindgren, K. (2001). Relationships among maternal–fetal attachment, prenatal depression, and health practices in pregnancy. Research in Nursing and Health, 24(3), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.1023

Lingeswaran, A., & Bindu, H. (2012). Validation of Tamil version of Cranley’s 24-Item Maternal– Fetal Attachment Scale in Indian pregnant women. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India, 62, 630–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-012-0175-3

Maddahi, M. S., Dolatian, M., Khoramabadi, M., & Talebi, A. (2016). Correlation of maternal-fetal attachment and health practices during pregnancy with neonatal outcomes. Electronic Physician, 8(7), 2639–2644. http://doi.org/10.19082/2639

Malenova, A. Y., & Kytkova, I. G. (2015). The relation to pregnancy, the child, motherhood of women in IVF situation. Pediatr [Pediatrician], VI(4), 97–104. (in Russian)

McFarland, J., Salisbury, A., Battle, C., Hawes, K., Halloran, K., & Lester, B. (2011). Major depressive disorder during pregnancy and emotional attachment to the fetus. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 14(5), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0237-z

McMahon, C., Gibson, F., Allen, J., & Saunders, D. M. (2007). Psychosocial adjustment during preg- nancy for older couples conceiving through assisted reproductive technology. Human Reproduction, 22, 1168–1174. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/del502

Muntaziri Niyya, A. F. (2011). To the communication problem between formation of attachment at children and health of mother. Vektor Nauki Tolyattinskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya: Pedagogika, Psikhologiya [Science Vector of Togliatti State University. Series: Pedagogy, Psychology], 4(7), 188–191. (in Russian)

Naku, E. A., Bokhan, T. G., Ul’yanich, A. L., Shabalovskaya, M. V., Tosto, M. G., Terekhina, O. V., & Kovas, Y. V. (2016). Psychological characteristics of women undergoing an IVF treatment. Voprosy Ginekologii, Akusherstva i Perinatologii [Gynecology, Obstetrics and Perinatology], 15(6), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.20953/1726-1678-2016-6-23-30 (in Russian)

Nyklček, I., Truijens, S. E. M., Spek, V., & Pop, V. J. M. (2018). Mindfulness skills during pregnancy: Prospective associations with mother’s mood and neonatal birth weight. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 107, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.01.012

Petrova, N. N., & Podolkhov, E. N. (2011). The mental status and personal psychological characteris- tics of infertile patients, treated by IVF. Zhurnal Akusherstva i Zhenskikh Boleznei [Journal of Obstetrics and Women’s Diseases], LX(3), 115–121. (in Russian)

Petrova, N. N., Podolkhov, E. N., Gzgzyan, A. M., & Niauri, D. A. (2013). Mental disorders and psy- chological characteristics of infertile women being treated with in vitro fertilization. Obozrenie Psikhiatrii i Meditsinskoi Psikhologii imeni V.M. Bekhtereva [V.M. Bekhterev Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology], 2, 42–49. (in Russian)

Punamaki, R.-L., Repokari, L., Vilska, S., Poikkeus, P., Tiitinen, A., Sinkkonen, J., & Tulppala, M. (2006). Maternal mental health and medical predictors of infant developmental and health prob- lems from pregnancy to one year: does former infertility matter? Infant Behavior and Development, 29(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.12.001

Qiao, Y., Wang, J., Li, J., & Wang, J. (2012). Effects of depressive and anxiety symptoms during preg- nancy on pregnant, obstetric and neonatal outcomes: a follow-up study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 32(3), 237–240. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2011.647736

Ranson, K. E., & Urichuk, L. J. (2008). The effect of parent–child relationships on child biopsychoso- cial outcomes: a review. Early Child Development and Care, 178(2), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430600685282

Robbins, E. (2003). Depression during pregnancy. http://drelizabethrobbins.com/depressionduring- pregnancy.htm

Savenysheva, S. S. (2018). Influence of the mother’s state and attitude to the child during pregnancy on the subsequent mental development of the child: an analysis of foreign studies. Mir Nauki [World of Science. Pedagogy and Psykhology], 6(1). https://mir-nauki.com/PDF/14PSMN118.pdf (in Russian)

Savenysheva, S. S., Anikina, V. O., & Blokh, M. E. (2022). Translation and adaptation of the Inventory “Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale” (MAAS). Konsul’tativnaya Psikhologiya i Psikhoterapiya [Counseling Psychology and Psychotherapy], 30(3), 92–111. https://doi.org/10.17759/cpp.2022300306 (in Russian)

Seimyr, L., Sjögren, B., Welles-Nyström, B., & Nissen, E. (2009). Antenatal maternal depressive mood and parental–fetal attachment at the end of pregnancy. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 12, 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0079-0

Shreffler, K. M., Spierling, T. N., Jespersen, J. E., & Tiemeyer, S. (2021). Pregnancy intendedness, maternal-fetal bonding, and postnatal maternal-infant bonding. Infant Mental Health Journal, 42(3), 362–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21919

Snaith, R. P., Constantopoulos, A. A., Jardine, M. Y., & McGuffin, A. (1978). A clinical scale for the self-assessment of irritability. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 132(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.132.2.164

Solovyeva, E. V. (2014). Developmental characteristics of children conceived by assisted reproductive technologies. Sovremennaya Zarubezhnaya Psikhologiya [Journal of Modern Foreign Psychology], 3(4), 33–48. (in Russian)

Stojnic, J., Radunovic, N., Jeremic, K., Kotlica, B. K., Mitrovic, M., & Tulic, I. (2013). Perinatal out- come of singleton pregnancies following in vitro fertilization. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology, 40(2), 277–283.

Talykova, L. V. (2008). Influence of risk factors associated with mother’s health on the development of pathological conditions in perinatal period in newborns]. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskoi Gosudarstvennoi Meditsinskoi Akademii im. I. I. Mechnikova, 4(29), 57–60. (in Russian)

Tomic, V., & Tomic, J. (2011). Neonatal outcome of IVF singletons versus naturally conceived in women aged 35 years and over. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 284(6), 1411–1416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-1873-2

Vasilenko, T. D., & Vorobeva, M. E. (2016). The quality of interaction between mother and child as a factor of formation of health. Pediatr [Pediatrician], 7(1), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.17816/PED71151-155 (in Russian)

Wilson, N., Wynter, K., Anderson, C., Rajaratnam, S. M. W., Fisher J., & Bei, B. (2019). More than depression: a multi-dimensional assessment of postpartum distress symptoms before and after a residential early parenting program. BMC Psychiatry, 19, Article 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2024-8

World Health Organization. (2018). Nurturing care for early childhood development: A framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf

Yakupova, V. A., & Zakharova, E. I. (2016). Features of inner position of mother in IVF women. Kul’turno-Istoricheskaya Psikhologiya [Cultural-Historical Psychology], 12(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2016120105 (in Russian)

Yang, S., Yang, R., Liang, S., Wang, J., Weaver, N. L., Hu, K., Hu, R., Trevathan, E., Huang, Z., Zhang, Y., Yin, T., Chang, J. J., Zhao, J., Shen, L., Dong, G., Zheng, T., Xu, S., Qian, Z., & Zhang, B. (2017). Symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy and their association with low birth weight in Chinese women: a nested case control study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 20(2), 283– 290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0697-2

Yazici, E., Yuvaci, H. U., Yazici, A. B., Cevrioglu, A. S., & Erol, A. (2018). Affective temperaments dur- ing pregnancy and postpartum period: a click to hyperthymic temperament. Gynecological Endocrinology, 34(3), 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2017.1393509

Alhusen, J. L., Gross, D., Hayat, M. J., Woods, A. B., & Sharps, P. W. (2012). The influence of mater- nal-fetal attachment and health practices on neonatal outcomes in low-income, urban women. Research in Nursing & Health, 35(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21464

Alhusen, J. L., Hayat, M. J., & Gross, D. (2013). A longitudinal study of maternal attachment and infant developmental outcomes. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(6), 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0357-8

Bahadırlı, A., Sönmez, M. B., Memi , Ç. Ö., Bahadırlı, N. B., Memi , S. D., Dogan, B., & Sevincok, L. (2019). The association of temperament with nausea and vomiting during early pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 39(7), 969–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2019.1581745

Belva, F., Henriet, S., Liebaers, I., van Steirteghem, A., Celestin-Westreich, S., & Bonduelle, M. (2007). Medical outcome of 8-year-old singleton ICSI children (born >or=32 weeks’ gestation) and a spontaneously conceived comparison group. Human Reproduction, 22(2), 506–515. https://doi.org/10.1093/Humrep/Del372

Bowen, A., Bowen, R., Balbuena, L., & Muhajarine, N. (2012). Are pregnant and postpartum women moodier? Understanding perinatal mood instability. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 34(11), 1038–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35433-0

Britto, P. R., Lye, S. J., Proulx, K., Yousafzai, A. K., Matthews, S. G., Vaivada, T., Perez-Escamilla, R., Rao, N., Ip, P., Fernald, L. C. H., MacMillan, H., Hanson, M., Wachs, T. D., Yao, H., Yoshikawa, H., Cerezo, A., Leckman, J. F., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2017). Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. Lancet, 389(10064), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3

Brunton, P. J. (2013). Effects of maternal exposure to social stress during pregnancy: consequences for mother and offspring. Reproduction, 146, 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-13-0258

Chen, C. J., Chen, Y. C., Sung, H. C., Kuo, P. C., & Wang, C. H. (2011). Perinatal attachment in natu- rally pregnant and infertility-treated pregnant women in Taiwan. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(9), 2200–2208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05665.x

Cildir, D. A., Ozbek, A., Topuzoglu, A., Orcin, E., & Janbakhishov, C. E. (2020). Association of prenatal attachment and early childhood emotional, behavioral, and developmental characteristics: A longi- tudinal study. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(4), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21822

Cranley, M. S. (1981). Maternal Fetal Attachment Scale (MFAS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t06786-000

Dawes, L., Waugh, J. J. S., Lee, A., & Groom, K. M. (2022). Psychological well-being of women at high risk of spontaneous preterm birth cared for in a pecialized preterm birth clinic: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open, 12(3), Article e056999. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056999

Dayan, J., Creveuil, C., Marks, M. N., Conroy, S., Herlicoviez, M., Dreyfus, M., & Tordjman, S. (2006). Prenatal depression, prenatal anxiety, and spontaneous preterm birth: a prospective cohort study among women with early and regular care. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(6), 938–946. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000244025.20549.bd

Della Vedova, A. M., & Burro, R. (2017). Surveying prenatal attachment in fathers: the Italian adap- tation of the Paternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (PAAS-IT). Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 35(5), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2017.1371284

Dokuhaki, S., Akbarzadeh, M., & Heidary, M. (2019). Investigation of the effect of training attachment behaviors to pregnant mothers on some physical indicators of their infants from birth to three months based on the separation of male and female infants. Pediatrics and Neonatology, 60(3), 324– 331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedneo.2018.08.002

Dokuhaki, A., Akbarzadeh, M., Pishva, N., & Zare, N. A. (2017). A study of the effect of training preg- nant women about attachment skills on infants’ motor development indices at birth to four months. Family Medicine & Primary Care Review, 19(2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.5114/fmpcr.2017.67864

Eastwood, J., Ogbo, F. A., Hendry, A., Noble, J., & Page, A. (2017). The impact of antenatal depression on perinatal outcomes in Australian women. PLoS ONE, 12(1), Article e0169907. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169907

Foley, S., & Hughes, C. (2018). Great expectations? Do mothers’ and fathers’ prenatal thoughts and feelings about the infant predict parent-infant interaction quality? A meta-analytic review. Developmental Review, 48, 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.03.007

Gracka-Tomaszewska, M. (2010). Psychological factors during pregnancy correlated with infant low birth weight. Pediatric Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism, 16(3), 216–219. (in Polish)

Hammarberg, K., Fisher, J. R., & Wynter, K. H. (2008). Psychological and social aspects of pregnancy, childbirth and early parenting after assisted conception: a systematic review. Human Reproduction Update, 14(5), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmn030

Hart, R., & McMahon, C. A. (2006). Mood state and psychological adjustment to pregnancy. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9, 329–337. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-006-0141-0

Hjelmstedt, A., Widström, A. M., & Collins, A. (2006). Psychological correlates of prenatal attachment in women who conceived after in vitro fertilization and women who conceived naturally. Birth, 33, 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00123.x

Hjelmstedt, A., Widstrom, A. M., Wramsby, H., Matthiesen, A. S., & Collins, A. (2003). Personality factors and emotional responses to pregnancy among IVF couples in early pregnancy: a compara- tive study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 82, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00040.x

Hompes, T., Vrieze, E., Fieuws, S., Simons, A., Jaspers, L., Bussel, J. V., Schops, G., Gellens, E., Bree, R. V., Verhaeghe, J., Spitz, B., Demyttenaere, K., Allegaert, K., den Bergh, B. V., & Claes, S. (2012). The influence of maternal cortisol and emotional state during pregnancy on fetal intrauterine body length. Pediatric Research, 72(3), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2012.70

Hopkins, J., Miller, J. L., Butler, K., Gibson, L., Hedrick, L., & Boyle, D. A. (2018). The relation between social support, anxiety and distress symptoms and maternal fetal attachment. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36(4), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2018.1466385

Hruschak, J. L., Palopoli, A. C., Thomason, M. E., & Trentacosta, C. J. (2022). Maternal-fetal attach- ment, parenting stress during infancy, and child outcomes at age 3 years. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(5), 681–694. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.22004

International Test Commission. (2017). The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (2nd ed.). https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation_2ed.pdf

Karatas, J. C., Barlow-Stewart, K., Meiser, B., McMahon, C., Strong, K. A., Hill, W., Roberts, C., & Kelly, P. J. (2011). A prospective study assessing anxiety, depression and maternal-fetal attachment in women using PGD. Human Reproduction, 26(1), 148–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq281

Keshishian, E. S., Tsaregorodtsev, A. D., & Ziborova, M. I. (2014). The health status of children born after in vitro fertilization. Rossiiskii Vestnik Perinatologii i Pediatrii [Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics], 59(5), 15–25. (in Russian)

Lindgren, K. (2001). Relationships among maternal–fetal attachment, prenatal depression, and health practices in pregnancy. Research in Nursing and Health, 24(3), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.1023

Lingeswaran, A., & Bindu, H. (2012). Validation of Tamil version of Cranley’s 24-Item Maternal– Fetal Attachment Scale in Indian pregnant women. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India, 62, 630–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-012-0175-3

Maddahi, M. S., Dolatian, M., Khoramabadi, M., & Talebi, A. (2016). Correlation of maternal-fetal attachment and health practices during pregnancy with neonatal outcomes. Electronic Physician, 8(7), 2639–2644. http://doi.org/10.19082/2639

Malenova, A. Y., & Kytkova, I. G. (2015). The relation to pregnancy, the child, motherhood of women in IVF situation. Pediatr [Pediatrician], VI(4), 97–104. (in Russian)

McFarland, J., Salisbury, A., Battle, C., Hawes, K., Halloran, K., & Lester, B. (2011). Major depressive disorder during pregnancy and emotional attachment to the fetus. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 14(5), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0237-z

McMahon, C., Gibson, F., Allen, J., & Saunders, D. M. (2007). Psychosocial adjustment during preg- nancy for older couples conceiving through assisted reproductive technology. Human Reproduction, 22, 1168–1174. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/del502

Muntaziri Niyya, A. F. (2011). To the communication problem between formation of attachment at children and health of mother. Vektor Nauki Tolyattinskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya: Pedagogika, Psikhologiya [Science Vector of Togliatti State University. Series: Pedagogy, Psychology], 4(7), 188–191. (in Russian)

Naku, E. A., Bokhan, T. G., Ul’yanich, A. L., Shabalovskaya, M. V., Tosto, M. G., Terekhina, O. V., & Kovas, Y. V. (2016). Psychological characteristics of women undergoing an IVF treatment. Voprosy Ginekologii, Akusherstva i Perinatologii [Gynecology, Obstetrics and Perinatology], 15(6), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.20953/1726-1678-2016-6-23-30 (in Russian)

Nyklček, I., Truijens, S. E. M., Spek, V., & Pop, V. J. M. (2018). Mindfulness skills during pregnancy: Prospective associations with mother’s mood and neonatal birth weight. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 107, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.01.012

Petrova, N. N., & Podolkhov, E. N. (2011). The mental status and personal psychological characteris- tics of infertile patients, treated by IVF. Zhurnal Akusherstva i Zhenskikh Boleznei [Journal of Obstetrics and Women’s Diseases], LX(3), 115–121. (in Russian)

Petrova, N. N., Podolkhov, E. N., Gzgzyan, A. M., & Niauri, D. A. (2013). Mental disorders and psy- chological characteristics of infertile women being treated with in vitro fertilization. Obozrenie Psikhiatrii i Meditsinskoi Psikhologii imeni V.M. Bekhtereva [V.M. Bekhterev Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology], 2, 42–49. (in Russian)

Punamaki, R.-L., Repokari, L., Vilska, S., Poikkeus, P., Tiitinen, A., Sinkkonen, J., & Tulppala, M. (2006). Maternal mental health and medical predictors of infant developmental and health prob- lems from pregnancy to one year: does former infertility matter? Infant Behavior and Development, 29(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.12.001

Qiao, Y., Wang, J., Li, J., & Wang, J. (2012). Effects of depressive and anxiety symptoms during preg- nancy on pregnant, obstetric and neonatal outcomes: a follow-up study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 32(3), 237–240. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2011.647736

Ranson, K. E., & Urichuk, L. J. (2008). The effect of parent–child relationships on child biopsychoso- cial outcomes: a review. Early Child Development and Care, 178(2), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430600685282

Robbins, E. (2003). Depression during pregnancy. http://drelizabethrobbins.com/depressionduring- pregnancy.htm

Savenysheva, S. S. (2018). Influence of the mother’s state and attitude to the child during pregnancy on the subsequent mental development of the child: an analysis of foreign studies. Mir Nauki [World of Science. Pedagogy and Psykhology], 6(1). https://mir-nauki.com/PDF/14PSMN118.pdf (in Russian)

Savenysheva, S. S., Anikina, V. O., & Blokh, M. E. (2022). Translation and adaptation of the Inventory “Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale” (MAAS). Konsul’tativnaya Psikhologiya i Psikhoterapiya [Counseling Psychology and Psychotherapy], 30(3), 92–111. https://doi.org/10.17759/cpp.2022300306 (in Russian)

Seimyr, L., Sjögren, B., Welles-Nyström, B., & Nissen, E. (2009). Antenatal maternal depressive mood and parental–fetal attachment at the end of pregnancy. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 12, 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0079-0

Shreffler, K. M., Spierling, T. N., Jespersen, J. E., & Tiemeyer, S. (2021). Pregnancy intendedness, maternal-fetal bonding, and postnatal maternal-infant bonding. Infant Mental Health Journal, 42(3), 362–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21919

Snaith, R. P., Constantopoulos, A. A., Jardine, M. Y., & McGuffin, A. (1978). A clinical scale for the self-assessment of irritability. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 132(2), 164–171. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.132.2.164

Solovyeva, E. V. (2014). Developmental characteristics of children conceived by assisted reproductive technologies. Sovremennaya Zarubezhnaya Psikhologiya [Journal of Modern Foreign Psychology], 3(4), 33–48. (in Russian)

Stojnic, J., Radunovic, N., Jeremic, K., Kotlica, B. K., Mitrovic, M., & Tulic, I. (2013). Perinatal out- come of singleton pregnancies following in vitro fertilization. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology, 40(2), 277–283.

Talykova, L. V. (2008). Influence of risk factors associated with mother’s health on the development of pathological conditions in perinatal period in newborns]. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskoi Gosudarstvennoi Meditsinskoi Akademii im. I. I. Mechnikova, 4(29), 57–60. (in Russian)

Tomic, V., & Tomic, J. (2011). Neonatal outcome of IVF singletons versus naturally conceived in women aged 35 years and over. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 284(6), 1411–1416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-1873-2

Vasilenko, T. D., & Vorobeva, M. E. (2016). The quality of interaction between mother and child as a factor of formation of health. Pediatr [Pediatrician], 7(1), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.17816/PED71151-155 (in Russian)

Wilson, N., Wynter, K., Anderson, C., Rajaratnam, S. M. W., Fisher J., & Bei, B. (2019). More than depression: a multi-dimensional assessment of postpartum distress symptoms before and after a residential early parenting program. BMC Psychiatry, 19, Article 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2024-8

World Health Organization. (2018). Nurturing care for early childhood development: A framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf

Yakupova, V. A., & Zakharova, E. I. (2016). Features of inner position of mother in IVF women. Kul’turno-Istoricheskaya Psikhologiya [Cultural-Historical Psychology], 12(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2016120105 (in Russian)

Yang, S., Yang, R., Liang, S., Wang, J., Weaver, N. L., Hu, K., Hu, R., Trevathan, E., Huang, Z., Zhang, Y., Yin, T., Chang, J. J., Zhao, J., Shen, L., Dong, G., Zheng, T., Xu, S., Qian, Z., & Zhang, B. (2017). Symptoms of anxiety and depression during pregnancy and their association with low birth weight in Chinese women: a nested case control study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 20(2), 283– 290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0697-2

Yazici, E., Yuvaci, H. U., Yazici, A. B., Cevrioglu, A. S., & Erol, A. (2018). Affective temperaments dur- ing pregnancy and postpartum period: a click to hyperthymic temperament. Gynecological Endocrinology, 34(3), 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2017.1393509